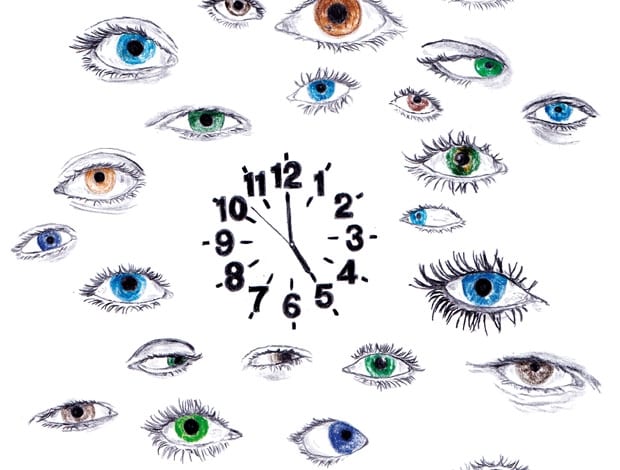

Plenty of managers still think that staff simply being present nine to five is enough to guarantee output. What will it take for them to stop clock-watching and start the workplace revolution?|‘New ways of working’ are given a bad rep as a way of squeezing more staff into fewer square metres, without any increase in effectiveness|Research shows that actual occupancy can be as low as 50 per cent – and every empty chair takes up an expensive chunk of ground rent|Hands off my stuff: staff are often unsettled by the idea of flexible workspace, seeing it as an erosion of their work identity. Once they’ve tried it, however, many don’t look back||

Plenty of managers still think that staff simply being present nine to five is enough to guarantee output. What will it take for them to stop clock-watching and start the workplace revolution?|‘New ways of working’ are given a bad rep as a way of squeezing more staff into fewer square metres, without any increase in effectiveness|Research shows that actual occupancy can be as low as 50 per cent – and every empty chair takes up an expensive chunk of ground rent|Hands off my stuff: staff are often unsettled by the idea of flexible workspace, seeing it as an erosion of their work identity. Once they’ve tried it, however, many don’t look back||

Elizabeth Choppin gets the lowdown on why, in the real world, the majority of offices in the UK are slow to adopt new ways of working

Flexible working, remote working, activity-based working, new ways of working – there is an exhausting amount of jargon to keep track of in the office industry these days. Buzzy ‘workplace revolution’ concepts have been alight for over a decade, and essentially they’re all variations of the same idea: a shift away from traditional work methods toward a more ‘anytime/anywhere’ approach to getting the job done.

The implications for building design, product design and how people relate to their employers have been very potent, exciting stuff – we’ve all been dazzled by the possibilities, and rightly so. But so far, there seems to have been an awful lot of talk and not quite as much action.

According to industry experts, vast swathes of the UK workforce are not benefiting from any of these new ideas – not even slightly.

“I would venture to say 90 to 95 per cent of office employees still work in the traditional way, with one-to-one desk allocation,” says Mat Oakley, a director of commercial research at Savills, an analysis supported by various other research specialists and workplace designers. A Practical Guide to Flexible Working, an imminent paper from the Original Creative Co-op, notes that only 48 per cent of employees in the UK are offered any sort of flexibility, compared to 90 per cent in mainland Europe.

The consensus is that adoption of new work methods has been sluggish in Britain and that most of the working population still has lengthy daily commutes, set workstations and a nine-to-five time structure. Outmoded styles of management place value on time in the office versus quality of output.

Plus, there is a shocking amount of organisations that do not prioritise offices with enough light, space and fresh air – or who aren’t willing to rethink their business strategies to allow for flexibility and choice. It seems daft when recent figures from the British Council for Offices say that the number of workplaces actually in use by employees can be as low as 50 to 60 per cent in a large sample of office buildings.

Considering the potential savings on premises costs and the established connection between a well-designed work environment and staff retention and creativity, the resistance to new ways of working is a puzzling state of affairs. So what gives?

Marie Puybaraud, who carries out workplace research for Johnsons Controls Consulting, puts it bluntly: “onoffice is a dream world. The reality is that most people don’t have access to those kinds of spaces.”

Which begs the question: what, or who, is standing in the way? The knee-jerk answer tends be that there is now a short supply of money in the coffers. But the problem can’t be solely a matter of resources, because some of the most forward-thinking workplace projects, particularly last year, were brought about with relatively little cash. There must be more to it.

A scratch below the surface reveals that, more than anything, fear and a lack of awareness might prove the biggest roadblocks to change – not to mention unenlightened executive boards and a simmering tension between designers and middle management.

Puybaraud agrees: “The major problem is organisations accepting change. The shift is very, very slow.” Although an obsession with the bottom line will likely inform decisions about how a workplace runs and will be fitted out, there is also an enormous lack of trust, she says.

Gill Parker, joint managing director of workplace design consultancy BDGworkfutures, believes there is a psychological hurdle to jump – people are very territorial.

“If you’re designing for a company that is trying to change to a more dynamic working model, then the trust issue becomes so much greater because it’s seen as having things taken away,” she says. “It becomes ‘What’s that going to mean for me and my team? Am I going to have to change my work pattern? Am I going to have a desk?’ People, management in particular, always think there is going to be a catch and they’re always looking for it.”

“Design is still considered by a lot of organisations as an add-on – something you do when you have extra money, as opposed to implementing a strategy”

There are ways of introducing change, however, if design consultancies are willing to push the agenda. In the case of the Communities and Local Government building in Victoria, BDGworkfutures eased the organisation into a more flexible way of working (chiefly, desk-sharing and collaborative work areas) with a pilot scheme for 140 of its 2,000 employees.

It was an ongoing process of monitoring and tweaking, says Parker, but it eventually proved to managers that it could succeed. “Clients very rarely want to be guinea pigs. Most times, they don’t want to be the boundary pushers, they want to go where others have gone before.”

Jack Pringle, co-founder of Pringle Brandon, believes the recession has dramatically changed the outlook and predicts a ‘wave’ of workplaces adopting new ideas. Facilities managers (FMs) are resistant though, he says, because ‘new ways of working’ became a sort of “messianic cause” in the last ten years.

Says Pringle: “It was almost like a religious cult – new ways of working is good for everybody – why aren’t you doing it? And the reality is it isn’t always good for everybody. There should be many variants of it but at the heart it just means looking at the real patterns of work without the assumption that the answer is one person to one desk.”

One tool for selling new ideas to businesses is the Workplace Performance Index used by Gensler, which analyses an organisation before and after occupying a new space. This sort of data has in many cases become the proof of the pudding, so to speak.

Jason Turner, interiors design director for Swanke Hayden Connell Architects, worries there isn’t enough of such data and that design teams are not brought to the table early enough. Using consultants from the very start will inform the decision-making process so that it delivers something other than the status quo, he says, but it doesn’t usually happen.

“There is still a lot of resistance to recognising that design is a business tool – how it can directly impact on performance,” says Turner. “It’s still considered by a lot of organisations as an add-on – something you do when you have extra money as opposed to implementing a strategy.”

He reckons the best projects are where CEOs have very clear objectives, see the value of design for their businesses and are willing to have it implemented properly. The ‘open plan’ mania of the last two decades failed in many cases because it wasn’t supplemented with enough alternative space for collaboration and ongoing change management, he says. Too often it simply meant more people crammed into smaller spaces in the name of progressive office design.

This is largely the fault of major decisions about offices only going as far as the finance director or the FM: “Their drivers are about money, not people,” says Turner. “When an organisation thinks about moving to a new space, it usually gets devolved to the FM – and this can crucially affect the way the business works. It doesn’t seem to register with senior management as something that deserves attention.”

There is very little evaluation, he adds, which is mind-boggling when companies are signing leases of up to 15 years that potentially cost millions.

Nigel Oseland of the Office Productivity Network agrees that there is a ‘disconnect’ between the bottom line and creating a better business. The two can work against each other, he believes, and this might be why so many offices stay stuck in the past.

“Whatever we say, the hidden agenda of flexible working is usually to save space and cost. The problem with that is, it’s treating the office as a cost burden, not as an asset that can benefit your organisation,” Oseland says. “So I don’t know whether it’s partly to do with the training of the corporate real estate team, the FM or their actual remit, which is to save money off the bottom line instead of meeting objectives like staff retention and well-being. The question is, how do you speak in the right language and convince the executive board that property can add a benefit and not just add a cost?”

“At worst, facilities managers should have a really good awareness of design and how it influences an organisation”

It’s the million dollar question, it would seem, and one that will be difficult to answer as businesses limp through the economic downturn. Oseland suggests organisations take a good, long look at their real objectives before plunging into new ways of working, or else it will backfire.

“The journey you have to take for flexible working is emotional and it’s hard work. If you’re not prepared to do it right from the start then don’t make that journey. There are other ways to save money. But if you are willing to do it right, the benefits are vast,” he says.

Part of that journey is a shift in middle management – moving away from clock-watching and presenteeism – and allowing staff a choice in when and where they’d like to work.

At the same time, flexible workers need a clear understanding of what is expected of them and how their work will be measured. It isn’t appropriate for every business all of the time – but certainly the notion of managers needing to see bodies at desks has been a hindrance to companies that might benefit (monetarily and culturally) from trying something new.

Activity-based working (no fixed desks and a variety of work settings in an office) is a natural progression for an organisation like Microsoft (onoffice May 09) because it wanted to showcase its technology. It made sense and the company has done it for nearly 700 employees in the Amsterdam HQ it opened last year.

But there are surprising success stories in other sectors such as banking – where the idea of having no designated desks and thousands of roving employees with laptops would have been laughed out of the boardroom five years ago. Macquarie Investment Bank’s headquarters in Sydney is a pioneering example (onoffice July 09).

In its new building, 3,000 employees choose from a number of work settings depending on specific needs and tasks – and a post-occupancy survey has revealed that 93 per cent of staff would never want to go back to desk ownership with fixed PCs. Storage space has been reduced by 78 per cent, lift use by 50 per cent and the premises saves 8,000 tonnes of carbon a year – but such a drastic change required letting go of virtually every established notion of what ‘a day at work’ means.

Philip Ross, CEO of Cordless Group and a consultant on the Macquarie project, says: “So many ‘new ways of working’ projects go wrong because they are attempts at desk sharing and they tend to ignore people in change management and technology.” People need to feel like they are being properly consulted and communicated with along the way, so that kinks can be ironed out.

Interestingly, Ross doesn’t believe that big corporations with budgets to match have an easier job of switching to activity-based working or other modes of flexible working.

“If you have a company with 200 people with laptops, it’s a much easier process,” he says. “You need to bring middle management along with you and encourage them to embrace the change, but IT people also put up barriers. You see breakout spaces that have no power and no connectivity, so if you’re sitting there, you’re seen as taking a break because you can’t actually work on a computer. There are so many things you’ve got to get right.”

Luke Pearson, of PearsonLloyd, challenges the notion of breakout spaces in themselves and suggests progress is stalled by a lack of innovative product design.

“Up to now there hasn’t been a product that has facilitated alternative work methods in a way that managers feel comfortable with,” he says. “The breakout area is a response because people desperately want to get away from their desks, but we should move on from it. The problem to date is that the solutions are reactionary – they’re geared toward very conventional reception and waiting area typologies that are expensive and not conducive to the working process. They’re too low, they’re not comfortable. This scenario quite often seems expensive because people can’t work effectively and managers see that.”Which leads back round to the question: can designers and management meet in the middle? Lots of designers seem willing to pass the blame on to both controlling middle management and procedural FMs.

Ian Fielder, CEO of the British Institute of Facilities Management, concedes that when an FM isn’t a strong influencer or decision maker, they probably will be risk adverse.

“They know that by not taking an innovative approach, they are on safe ground and ensure that they can deliver. I would say that is a changing situation, but I understand the criticism and I’d say that in some cases it’s true,” he says. “You could go to a very staid insurance company and see the FM perhaps not be a support in moving the organisation forward in terms of its work strategy.

Fielder suggests that we be patient because the FM profession is young – it is currently morphing from an older generation who know about safety regulations and hard services, like the boiler-room and air conditioning, into a younger, savvier set who gain qualifications in their field and seem much more in tune with the wider goals of a business.

“At worst, facilities managers should have a really good awareness of design and how it influences the culture of an organisation. That’s just as important to the FM role now as the boilers were 15 years ago,” he adds, citing Bloomberg and Cisco’s office buildings as examples of how dynamic facilities management can be. “But there are as many buildings where the FM may be struggling to understand a new concept. So it’s about educating the FM to recognise how it adds value to the business. I wish I could say that it was all done and dusted and that we were there. Clearly we’re not, but the trend is that we’re slowly getting there.”