Nooks and crannies may look good, but they can attract the wrong sort|Tamir Addadi’s Nairobi office complex wont be behind gates and fences|A lack of “dead areas” mean that crime is much harder to commit|At Heron Tower, an enormous fish tank disguises scary X-ray equipment|In the event of a blast, Heron Tower’s facade will act like a net|“Sentry planters” with steel frames can withstand the force of a car|Planters in situ at Canary Wharf – the friendly face of defensive space|St Helier’s new Esplanade Quarter, masterplanned by Hopkins Architects|Depite its appealing looks, terrorism is seen as a genuine threat to the safety of the Jersey development||

Nooks and crannies may look good, but they can attract the wrong sort|Tamir Addadi’s Nairobi office complex wont be behind gates and fences|A lack of “dead areas” mean that crime is much harder to commit|At Heron Tower, an enormous fish tank disguises scary X-ray equipment|In the event of a blast, Heron Tower’s facade will act like a net|“Sentry planters” with steel frames can withstand the force of a car|Planters in situ at Canary Wharf – the friendly face of defensive space|St Helier’s new Esplanade Quarter, masterplanned by Hopkins Architects|Depite its appealing looks, terrorism is seen as a genuine threat to the safety of the Jersey development||

As building security moves higher up the agenda, how can architects find ways to create environments that are safe, without resorting to barbed wire and blank walls?

The world is increasingly paranoid. The irrepressible rise of CCTV suggests the revolution will indeed be televised, just on rather grainy footage. A timely affirmation of this came last March when tens of thousands marched in protest against government spending cuts.

It was a passionate but generally well-mannered affair, concluding in Hyde Park where the Labour leader Ed Milliband addressed the crowd. But elsewhere in London trouble was brewing: global banks HSBC and Santander had their perimeters breached by an angry mob whose Saturday morning manoeuvres, on this occasion, extended a little further than checking their balance. It is proof, if it were needed, that security is an ever more important element in the design of a building. Determining the risks involved to particular development requires an understanding that goes beyond more traditional architectural concerns of orientation and context. At the moment, banks are about as popular as Nick Clegg, and one suspects few tears were shed over some relatively small-time defenestration. Equally, it’s not everyday that anarchists go on the rampage in central London, but as the City of London police’s architectural liaison officer (who asked not to be named) notes it helps to know your enemy. “There is no point in recommending architects defend against treason and piracy if there is no history of treason and piracy in the area,” he asserts.

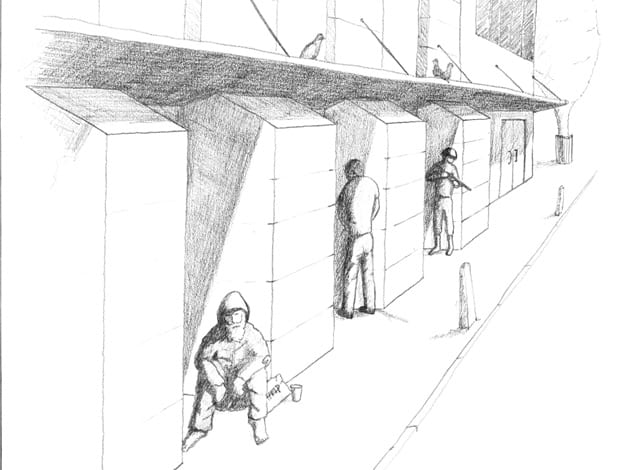

Every force has an architectural liaison officer (ALO); they usually deal with developments at the pre-planning stage where architects are looking for advice, or they look at planning applications that have already been submitted. The process begins with a crime pattern analysis: once the threats are identified, counter-measures can be included in the design. Picking the brains of your local ALO can be an invaluable source of local knowledge. The City of London’s ALO spent several years policing the Square Mile, for example. “People round here use the buildings during the day, and often the architects do not consider what is happening at night,” he says. “A building might have lots of niches and blind spots that might look good in the drawings, but can actually become hiding places for people up to no good, or informal public lavatories.” Architects rarely seem to design buildings with full-bladdered ne’er do wells in mind – but perhaps they should, as it’s heartbreaking to see a beautiful object turned into a giant public toilet.

Those searching for their local ALO can find them on the Secured by Design website, where many industry standards for securing a building are pulled together. This not-for-profit organisation is owned by Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO). The body has its own security certifications and awards although, like ALOs, it has no statutory powers.

It’s not just the building itself that needs to be considered – the surrounding space can be an equally effective weapon. In the Kenyan capital of Nairobi, street crime is a serious problem, so much so that almost all office development exists behind gates and fences. When commissioned to design a large office scheme in a bustling part of the city, London-based practice Tamir Addadi Architecture proposed a more public-spirited answer. “When you visit a building closed off by fences

it doesn’t seem to be a very good environment to work in,” says Tamir Addadi. “We concluded that if we added some shops and cafes, these commercial buildings could serve the street as well as the offices.”

The buildings overlook a central garden space which features an all-too-rare Wi-Fi connection intended to draw in nomadic workers as well as shoppers from the street. Interspersed throughout the square are three office blocks, their rooftop gardens doubling as impromptu lookout towers. “It will be a very intensively used space,” says Addadi. “There are no dead areas. You only need lots of security guards if people can commit a crime without being noticed.” It’s a solution bound to please the proponents of public space in commercial developments, but even Addadi admits it’s a radical proposal in such an area. “It is a very simple idea and we hope it would work.” He needn’t wait long to find out, as the development is scheduled for completion in the latter part of 2011.

On this occasion it was the architect that convinced the developer to attack the security problem more laterally, but as KPF’s managing principal Paul Katz says, security measures are typically driven by the client. Unsurprisingly, a vibrant public space is not always the most pressing concern. “Mixed-use projects can be used in this way to control petty street crime,” he says. “But this can make it easier for more serious infiltration. Some large tenants prefer to have nothing on the base floor so they can truly protect their building from threats.” This siege mentality is more likely in countries unsympathetic to the presence of western multinationals.

Jim Whitcomb, head of security at global engineering giants WSP Engineering, says that a building’s occupants impact hugely on security risks. Prior to Libya’s implosion, the company was working on three sizeable developments there including two commercial towers. One of the first questions Whitcomb asked was who was using them. “If it’s a local telecoms firm, then it should be no problem. If you are going to ship in IBM, that’s a different matter.”

Whitcomb likens modern-day developments to the medieval castles of yore. “It is about keeping the enemy as far away as possible through defensive space.” Defensive space generally means bollards or planters designed to prevent a car bomb attack. Unlikely, it would seem, but their very presence indicates a deeper challenge to architects. No practice harbours a burning desire to build a fortress, and so the balance must be struck between adequate protection and imposing citadel.

KPF trod this tightrope with aplomb with its recently completed Heron Tower in Bishopsgate. The 242m-high edifice has won plaudits for its transparency and openness at street level. The firm’s Paul Simovic explains: “There is a cable tension facade, which, if there was an explosion, would stop the whole thing caving in. It works like a net. If we’d done it any other way you would have ended up with such large mullions it would have ruined the transparency of the space.” Similarly, unsightly X-ray equipment is tucked away behind the lobby’s enormous fish tank.

In another financial hub not so far away, Stephen Izatt is wrestling with the issue of terrorism. This isn’t the Middle East: it’s Jersey, and Izatt heads up the Waterfront Enterprise Board overseeing a new banking quarter masterplanned by Hopkins Architects. Blast curtain walls and reinforced columns are just two measures under consideration, which seems surreal for a sleepy backwater off the French coast. Still at the preliminary design stage, one senses it will be a long process. “I’d love to meet an architect who understood this particular problem,” says Izatt. “But it is not top of their agenda.” Agendas change, though, and security is a more pressing question than ever. How elegantly that question is answered rests with architects.