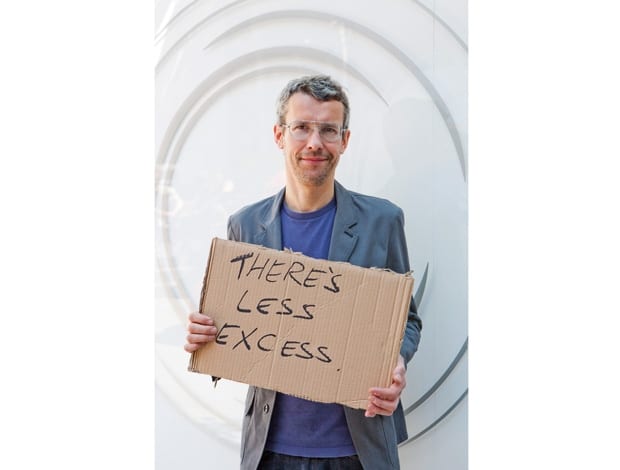

Michael Marriott|Kirsty Whyte|Marcus Ludwig|Lighting designer Jake Dyson|Anthony Dickens|Max Fraser, contributing editor of DeTnk|Tom Dixon|Paul Simmons|Nika Zupanc with a quote from Virginia Woolf|||

Michael Marriott|Kirsty Whyte|Marcus Ludwig|Lighting designer Jake Dyson|Anthony Dickens|Max Fraser, contributing editor of DeTnk|Tom Dixon|Paul Simmons|Nika Zupanc with a quote from Virginia Woolf|||

Kerstin Zumstein roams the streets of Milan during Design week and asks designers what they think the lasting effects of the financial crisis will be on design

Photos by Ed Reeve

It’s that time of the year again: Milan! The world’s design aficionados go on their annual pilgrimage to I Saloni and, increasingly, to see the satellite events that take place around the city during the festival of design.

Yet this year is not like any other year. This year, the world has been tainted by the global recession. What started as a financial crisis has since seeped through into every industry spreading fear of a depression and most certainly questioning our world as we know it. So how does Milan with its famed decadence, glitz and glamour fit into this climate?

This issue of onoffice clearly shows how a pared-back approach is becoming commonplace in workplace design. We call it austerity deluxe, as it uses recycled and salvaged materials without compromising a chic design aesthetic.

Yet while all projects demonstrate different ways to achieve this, they all share a common denominator: a shortage of new furniture being specified. So as the sexy event invites for Milan started fluttering through the mail box just like any other year, onoffice wondered if a furniture design show like I Saloni still had a place in the current climate or if it’s opulence would be considered vulgar in light of the crash?

So, I packed my bags and flew over to Italy for a week of intense design trend scouting, shameless networking and, moreover, to investigate the effect of the recession on Milan.

Many, like Konstantin Grcic for instance, think that the effect will be more evident next year because the crisis came at such a pace.

“Most products were already in production before it hit,” he points out.

But people said the same at Orgatec end of last year, and nonetheless evidence of a shockwave hitting the office market was already present. In Milan to the contrary I found a new air of optimism.

“To be honest,” Grcic continues: “I looked forward to the fair in this crisis. Things are more focused now, there is more discussion. Just because there is less money doesn’t mean there is no money. Instead clients are more careful about where they spend, more interested in investments and that in turn encourages more quality and intelligence in design.”

“Things are more focused now, there is more discussion. Just because there is less money doesn’t mean there is no money”

Grcic is not alone in feeling this sense of opportunity. French designer Matali Crasset is glad Milan is becoming less superficial, returning to being more concentrated on product than party. “The crisis will bring Milan back to what it’s for: presenting good new designs!”

There were a lot of slogans like ‘back to basics’ which stand in line with the rise of stripped-back designs and the utility theme found in the many cardboard projects. Most designers however don’t like the rhetoric of regression claiming it’s about using raw materials but in an advanced way.

Interni magazine wrote about Tom Dixon’s new collection: “It’s topical due to the back to basics theme”. Yet Dixon says he has always used industrial materials. “My inspiration was the heritage of industrial England from the start. I use copper because it’s underused and I like the way it changes colour in temperature. There is a reason behind the choice which has nothing to do with whether it’s fashionable.”

Dixon’s roots have always been in metal work, his collections always monochrome, but what makes it so topical right now is the honesty and simplicity of his designs and the way he focuses this year on highlighting the imperfections of the materials – for example the bubbles in the heavy duty, pressed glass, that are highlighted when his new lamps are switched on.

On the other end of the material spectrum is gold. It stands in clear contrast to all the wood and cardboard products that are so popular right now, and emphasises the polarisation in the market place. As with many other industries the low budget products and the high-end luxury items are the ones that will survive and dominate during the downturn.

Mark Holmes from newly launched micro brand Minimalux, stirred a lot of controversy with his collection of desk accessories and vessels made of gold.

He says, “In future the only place you can achieve big margins is the high-end market, it’s the only customer base that will allow you to retain manufacturing in the UK. I don’t think austerity chic is the way to go as it’s just a temporary solution.”

Ironically, Holmes had already developed the idea of golden gift items for his launch collection before the recession hit: “But then I realised it’s even more relevant now because the collection is about longevity – the opposite of our previous throw away culture. I wanted to make products that have a silent design approach – a polite form of bling if you like! – yet convey timelessness.”

Hard times are usually good for gold as it’s deemed recession-proof. The price has been buoyant for some time and the fact that less gold is produced each year helps keep the prices high. Holmes is playing on the upsurge of consumers wanting to invest in something that retains its value, to buy something you can pass on through generations, a phenomenon recently termed ‘heirloom design’ by innovator/inventor Saul Griffith.

“Back to basics is certainly not the way out of the recession. It’s not a time to be nostalgic. We need to be proactive, keep pushing for innovation and take risks”

The concept of timeless designs obviously isn’t new, and designers like Sam Hecht and Jasper Morrison who have stuck to their simple ‘normal’ designs unaffected by trends and fashion crazes, once again stood out at the fair – Hecht with his Table, Chair, Bench for Established & Sons and with Morrison his Trattoria chair for Magis.

Alasdair Willis, Director of Britain’s most luxurious furniture brand, Established & Sons, says: “Back to basics is certainly not the way out of the recession. It’s not a time to be nostalgic. We need to be proactive, keep pushing for innovation and take risks. The reproduction of countless variations of the same design doesn’t hold much credibility right now and thankfully we are already seeing the endless flirtations of the same theme disappearing.”

In response to whether the use of tulipwood (a filling wood most commonly found in furniture and rarely exposed) to exhibit their collection is playing on the boarded up reality of current high streets, Willis points out that Established showed Morrison’s Crates three years ago so this design language is not a reaction to the crisis. “Now is a time where we need to readdress our clients, we can’t rely on retailers to do that as they are struggling. It’s about refocusing your distribution plan.”

In keeping with his interdisciplinary design milieu Willis quotes Galliano during fashion week who said: “It’s a credit not a creative crunch!”

But is this really the case? Hasn’t the design industry long been suffering from complacency?

Grcic believes the creative crisis was a long time coming: “There was so much of everything. It was time for a change. In the next few year we’ll see designers doing less but better!”

Fellow German designer Stefan Diez also believes quality is key. “Just to consume more is not the way out, we need to consume better. The reason why there is no one on the streets despite the severity of the crisis is because it’s our fault, we let it happen. That’s why I don’t think there will be a revolution. Today’s designers don’t want to be political. Superficial words for super cool projects have ruled over the past decade. Now designers, and I include myself here, are scared of loosing that freedom and lightness we’ve been enjoying.”

Diez thinks the amount of prototype designs that are made just for the show and then binned need to be reduced. “Too many companies were going for the show value effect of prototypes that never make it into production. What’s the point? Industrial production needs to be rethought. E15 for instance are making things with hand labour and only very little tooling maybe that’s a possible solution to creating more value.”

Vitra, on the other hand, are using the current climate as an opportunity to invest in tooling and R&D, ‘like a gap year’, Joanne Moore, Vitra’s UK PR manager, says.

It was noticeable that Vitra have changed the style of their stand. Instead of showing loads of prototypes they are launching only one product; the Bouroullec’s Vegetal chair, and all other products on the stand were ready to order. Young companies like Minimalux are trying to keep tooling costs down, and run on the skeletal basis of produce on demand.

New French furniture company Moustache launched with a mission statement highlighting past values and heritage, a far cry from the terms ‘fresh’ and ‘innovative’ so popular in the marketing lingo of recent years. Moustache states: “Rather than artificially developing the principle of novelty at any price our products attempt to take advantage of passing time to give them a little of the heritage value that furniture and objects hold in the past”. So maybe a sense of nostalgia after all?

Nigel Coates, whose new lamp range for Slamp at Euroluce was appropriately marketed as ‘luxury on a budget’ believes utility doesn’t need to mean a trashy look. “When I was a child functional clothing and furniture still had chic! To contrast with the period of opulence we’ve just come through we need thoughtful design. That doesn’t mean you can’t use gold, crystal and sparkle. It’s important that designs aren’t gimmicky but instead have both lightness and gravitas in spirit!”

Pearce from Designers Block simply hopes the crisis will shake up the top-down hierarchy of so many companies: “I hope that designers can genuinely be more creative now, rather than having to settle for the ‘oh, now we get it, so it can go into production’ compromise!”

I don’t know if it was the sunshine or the surprise at the unexpected amount of yummy canapés but the fact is most people at Milan this year felt optimistic about the future. A welcome break from the doom and gloom back home, it was reassuring to hear so many designers genuinely proclaiming that the crisis is a much needed opportunity for design to redefine itself.

“Of course”, Tom Dixon concludes, “there were a lot of things wrong with Milan. Now we’re suffering the hangover of previous years. Design had generally become a bit lost and cynical when brands like Swarovski latched on to the design boom to get editorial. But after being the poor relation to fashion for so long, the parties and endlessly flowing champagne that came with the furniture boom were symptoms of its eventual recognition. I enjoyed it!”

And to be honest, who didn’t?