Ste. Marie’s unconventional pilates and yoga studio in Vancouver is designed to lead its visitors on a theatrical journey to the heart of the body

In the midst of the densely populated Vancouver neighbourhood of Yaletown, in between a high-end grocer and an uptown salon, Ste. Marie Design has reimagined a yoga studio as an urban womb.

Jaybird, the first venture of the appropriately named pilates instructor Ariel Swan and her yogi partner Barbie Bent, encourages patrons to “get out of your head and into your body”. To that end, a tightly choreographed 227sq m space, inspired by the yogic principal of flow, the dance work of Lucinda Childs and Yvonne Rainer and even the animate sculpture of Constantin Brâncuşi, offers intuitive pathways to the inner self.

The transition from the street is a dark, almost anonymous-feeling entranceway painted black. Once inside, patrons are embraced by a welcoming earth-toned common area and front desk that is part art gallery, part gathering and part retail space. A theatricalised proscenium leads the way into the studio itself, painted black, and devoid of mirrors but for a reflective ‘altar’ full of candles, the instructor’s lair.

Here built-in wall stereos provide an audio immersive experience in which to exercise, in candlelit darkness with infrared heat. The embryonic experience is part sensory deprivation tank, part meditative journey – and one that is increasingly popular in these fraught times. Swan says that the articulation of three distinct spaces has actually assisted with physical distancing requirements, as the studio reopens at a third of its capacity. “The layout allows clients to wait in line without feeling cramped and avoids bottlenecks,” she says.

The new design replaces an existing studio of uninspired drywall painted white and bare industrial style ceilings, in an old 1930s warehouse – the kind that proliferated when the area was called Railtown, before becoming a des res destination in the 90s. But as with so many of Ste. Marie’s designs, this one is the antithesis of the generic, bare-boned West Coast minimalism that founder Craig Stanghetta likens to “an architectural recipe out here”.

With the firm’s focus on creating a sense of ‘authenticity’ and ‘individual narrative’, it rejected the anonymous all-white transparency that is so commonly found in yoga studios, in favour of one that feels – as does the firm’s Chinatown restaurant Kissa Tanto – like a hidden treasure. Hospitality, says Stanghetta, is in Ste. Marie’s DNA, and a welcoming element is key – whether designing an eatery or a workplace or a workout space. In the new pandemic reality, it’s all about creating spaces “where people want to be”, he notes. Ultimately, it’s about designing desire.

But for a tiny Jaybird sign outside, this is not a place that advertises itself. “You feel like you have to find it,” says Stanghetta, “you have to arrive here through a sequence of spaces – it’s tucked away.” Still the unconventional yoga studio, he maintains, has a point of view and an irreverent attitude. “It’s more like a restaurant or a club,” says the designer who has created many. “It has its own personality.”

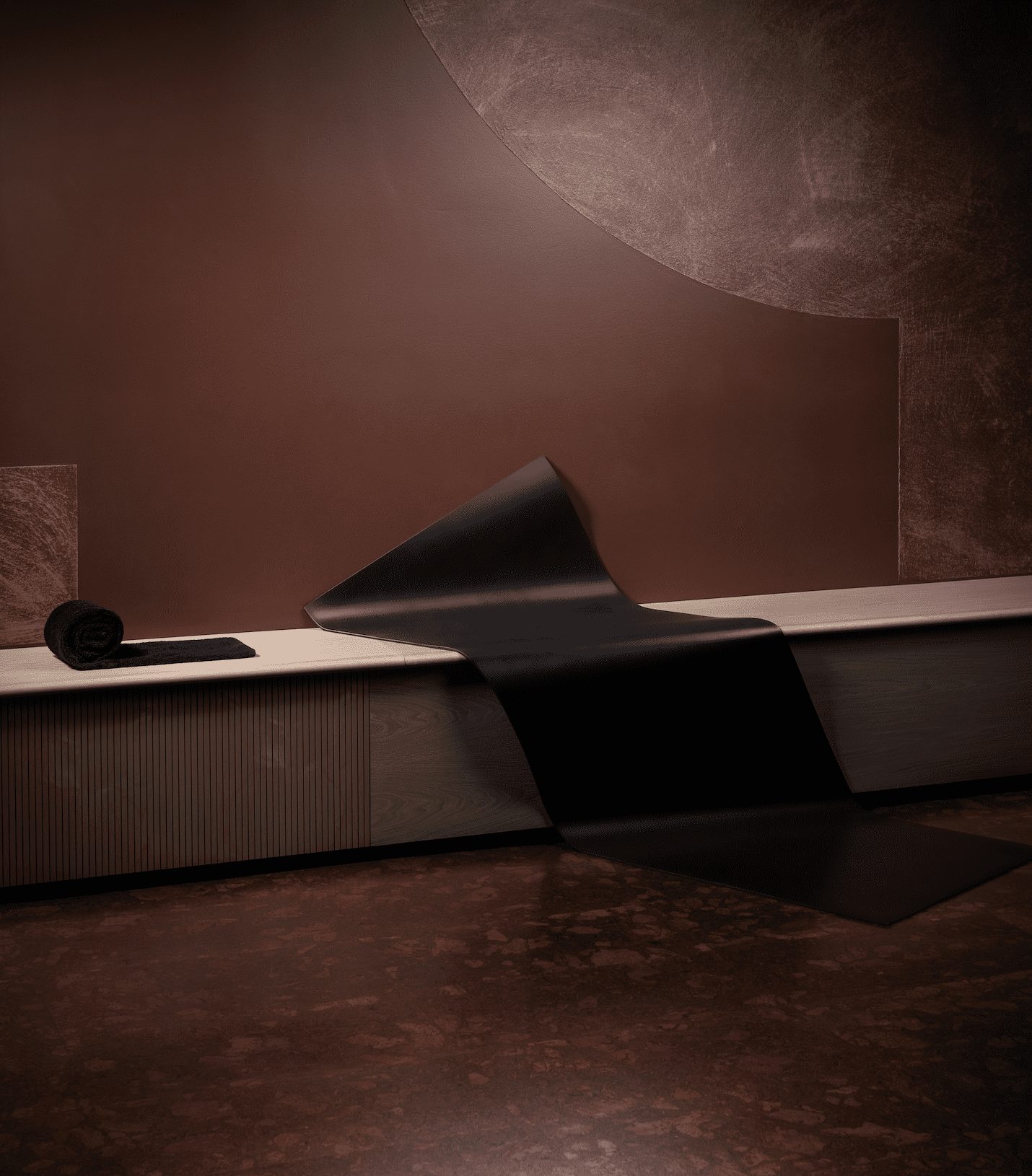

As led by project designer Jessica Bell, that personality is expressed in striking ways that make the most of a limited space and budget. The common area’s palette of browns from chestnut to mocha, meant to evoke skin colour, is graced by cork flooring throughout, its mottled natural patterning like an earthy marble. As one enters, the eye is drawn to the front desk of white-painted millwork and vertically striated charcoal pole wrap. A trapezoidal dark glass installation angled to resonate with the similarly shaped Jaybird motif – conceived by Glasfurd & Walker – hangs above it in a neon-lit plexiglass box.

The semi-circular room boasts similar geometric patterning as well as three distinctive works by London- based artist Adam Hale, chosen for their subversion of traditional ideas of beauty and body image officially shunned by the ‘inclusive’ mirror-free studio as well as their surreal ‘get out of your head’ qualities. One is a dadaesque figurative collage of what could be a stereotypical West Coast girl, deconstructed; another is a female head topped by an emerald plate and a glass-plated cover; a third shows a red-painted female lip, and scarlet-coloured fingernails with hawk’s feathers coming out of them. The works are strategically lit with overhead spotlights that cast a warm glow on the cork walls.

Behind the front desk, deep cabinetry masked by a faceted cork wall articulated by integrated one channel LED lighting has been carved out of the existing space. On the northern edge of the desk area, a vulvic vase filled with salmon-hued bulrushes appears as though pulled out into 3D form, while its south side is articulated by a theatrical proscenium sliced in half, breaking the fourth wall between patron and space.

Once inside the all black – but for the repeated cork-clad wall with LED lighting at the candle covered ‘altar’ – studio, the dreamlike sequencing continues. Pared down to its bare essentials, with the original 1930s oak flooring revealed, the room reflects the desired inner process of the practitioner. “We want clients to be able to find themselves and be themselves here,” says Swan of a studio that in the absence of light and mirrors is all about the haptic experience.

“This space,” says Stanghetta, “is about being out of space. When all the lights are off, you’re just floating in there.”

All images by Conrad Brown

As featured in OnOffice 152, The Now Issue