|The DYB centre de competénces, a skills centre for watchmakers|Exhibition design for the winners of 2005’s Swiss Federal Grants for the Decorative Arts|Allegro lights for Foscarini|Oasis cafe chair and table for Moroso|Reel for B&B Italia is made from string woven taut around a frame|Oïphorique, a light installation that expands and contracts like a sea creature|Theatrically spinning fabric pendants make up Les Danseuses|Ruckstuhl’s Silento panel|Furniture brand USM’s stand in Milan, festooned with strings of ball bearings||

|The DYB centre de competénces, a skills centre for watchmakers|Exhibition design for the winners of 2005’s Swiss Federal Grants for the Decorative Arts|Allegro lights for Foscarini|Oasis cafe chair and table for Moroso|Reel for B&B Italia is made from string woven taut around a frame|Oïphorique, a light installation that expands and contracts like a sea creature|Theatrically spinning fabric pendants make up Les Danseuses|Ruckstuhl’s Silento panel|Furniture brand USM’s stand in Milan, festooned with strings of ball bearings||

Swiss architecture and design studio Atelier Oï begins its projects, be it a perfume bottle or building, on an elemental level

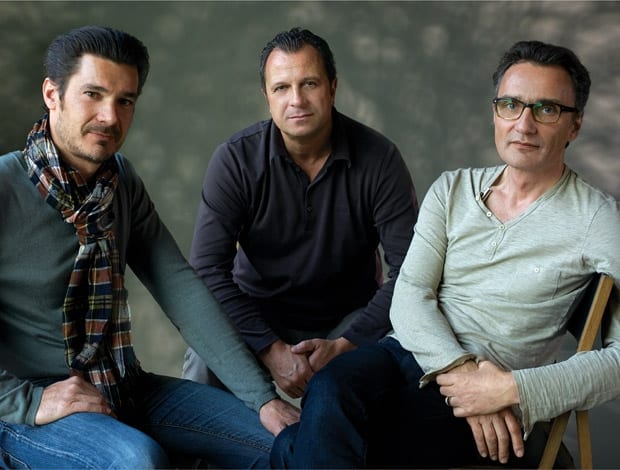

At its studio in La Neuveville, Switzerland, 23-year-old design and architecture practice Atelier Oï has a library of 20,000 materials and prototypes. Aurel Aebi, one of the three founders, likes to compare it to a cupboard of chef’s ingredients.

“Like a cook in a kitchen, or at a market, we go down to this ‘materiotheque’ and come up with our first studies for a project,” he says. “It’s a pool for ideas.”

Aebi founded the practice with Patrick Reymond, a fellow student at Lausanne’s Athenaeum architecture school, and Armand Louis, a ship builder, in 1991. It has since grown to a team of 40, based in a 900sq m former motel – punningly renamed The Moïtel – working on projects ranging from perfume bottles, lights and furniture, to shops, boats and buildings.

At the root of each project, Aebi explains, is a micro examination of materials. In its 2012 book, Atelier Oï: Workshop Guide, the studio compares its almost obsessive archiving habits to that of a biologist collecting minerals and experimenting with how to manipulate their aesthetics.

“Every structure needs a specific material and not every material can be processed in the same way,” the book states. “Basic techniques such as weaving, folding, coiling and bending determine the visual quality and impression of the structures.”

The tome explores Atelier Oï’s workshop-based development process, showing how its designs begin by first zooming into the finest details and qualities of a material, gradually building a larger composition. This is typified by the DYB centre de compétences office building in Switzerland, a training centre for watchmakers, owned by the Swatch group. With its facade of circular openings akin to a mass of bubbles, the design works in micro and macro scale, adding texture and giving the building translucency. The book goes some way to explaining the studio’s ability to try its hand at just about anything.

onoffice met the Atelier Oï trio (named after the Russian word ‘troika’, a carriage pulled by three horses) in Milan, where the studio is launching several new projects. The Silento acoustic panel for Ruckstuhl is inspired by school satchels, with two straps across its body that make a pleasing design detail of the apparatus used to hang it from the ceiling. “Just as you have commas and points in a sentence, the privacy panels are punctuation for office space,” is the way Aebi poetically describes the product.

Also being launched is the Embrasse chair for Driade, which has a minimal wood frame that plays on the intersection of two curved lines in the seat back; glassware for Venini; a range of rugs, also for Ruckstuhl; additions to its Hive range for B&B Italia; a light for Illuminartis; and additions to its Oasis range for Moroso.

The Oasis sofa (first shown last year) has a steel backrest and frame, which loops around a loose piece of fabric to hold it in place, allowing the fabric to be easily removed. This year, the studio has created the Oasis cafe table and chair with the same freeform linear frame, giving the familiar cafe chair a bit more personality.

“You see this type of chair a lot,” says Aebi of the new table and chair, “but this one is asymmetric and more free. It’s like calligraphy writing.” It also plays with convention, he explains, pointing to the Oasis sofa. “Normally on sofas, the lines really finish the furniture, but here, the definition of form is done in a fresh way. The fabric is spilling out of the lines.”

The studio has a way with lines. Aebi describes its basic ethos as “thinking with our hands,” using bits of wire to mock up ideas, and closer examination of its best-known projects hints that many have started life this way. In product design, its Allegro lamp for Foscarini is a collection of individually angled metal rods, which, grouped together, create a bold profile. Its Reel seat and table for B&B Italia is, again, a simple shape given pattern by its structure of criss-crossed woven string.

This theme has been upscaled to the practice’s installations, such as A Composition of Cords (2006), an exhibition at Centro Culturale Svizzero in Milan, where flexible cord was sculpted into rigid 3D forms, and Gros de Vaud House in Switzerland (2008), where twists of the structural beams create subtle definition in the facade.

In its immersive installations Atelier Oï is perhaps most accomplished, which has led to many retail design partnerships with the likes of Rolex, Hermès and Swatch. Its Oïphorique light installation, created to mark the studio’s 20th anniversary in 2011, had totem-pole-like towers of billowing lanterns, that expanded and contracted hypnotically like jellyfish. It was later reprised for an exhibition of Bulgari watches. Another exhibition, Les Danseuses, created to coincide with the inauguration of the Moïtel in 2009, featured red fabric pendant shades spinning theatrically like skirts.

In Milan this year, the team also designed stands for bathroom company Laufen, a softly lit, pure white space, and furniture brand USM, a black booth decorated with strings of beaded metal curtains (the ‘beads’ are actually the ball bearings used in the company’s storage systems).

Being so multidisciplinary could spread a studio’s output too thinly, but Aebi says that his firm’s wide variance of projects is now its selling point. “What’s interesting is that clients now come to us because we are not specialists. They like to understand how we think about a new theme. We can look at it from the outside.” He describes himself and his cohorts as in-betweeners, switching between languages (French and German), hopping from one discipline to another, giving them an objective viewpoint.

At the moment the team is working on a tablet design for a well-known technology brand – something completely different to previous work, but to Aebi, it’s all interlinked.

“One project inspires another, one discipline crosses another. When you are (a team of) three, it’s constantly interactive and responsive; there’s always an exchange of ideas. It’s not a one-man show.”