The Paris-based co-living and co-working experts have created a manifesto that explores how our lives will change post-Covid, beyond architecture and design

Acknowledging how physical distancing will likely transform how we live and work, the ‘Together Has Changed’ manifesto by Cutwork examines the more typical themes of office and home-working, as well as how our most intimate relationships may change. In this exclusive excerpt from Cutwork’s manifesto, we take a closer look at how our life might look like in the future.

Together has changed

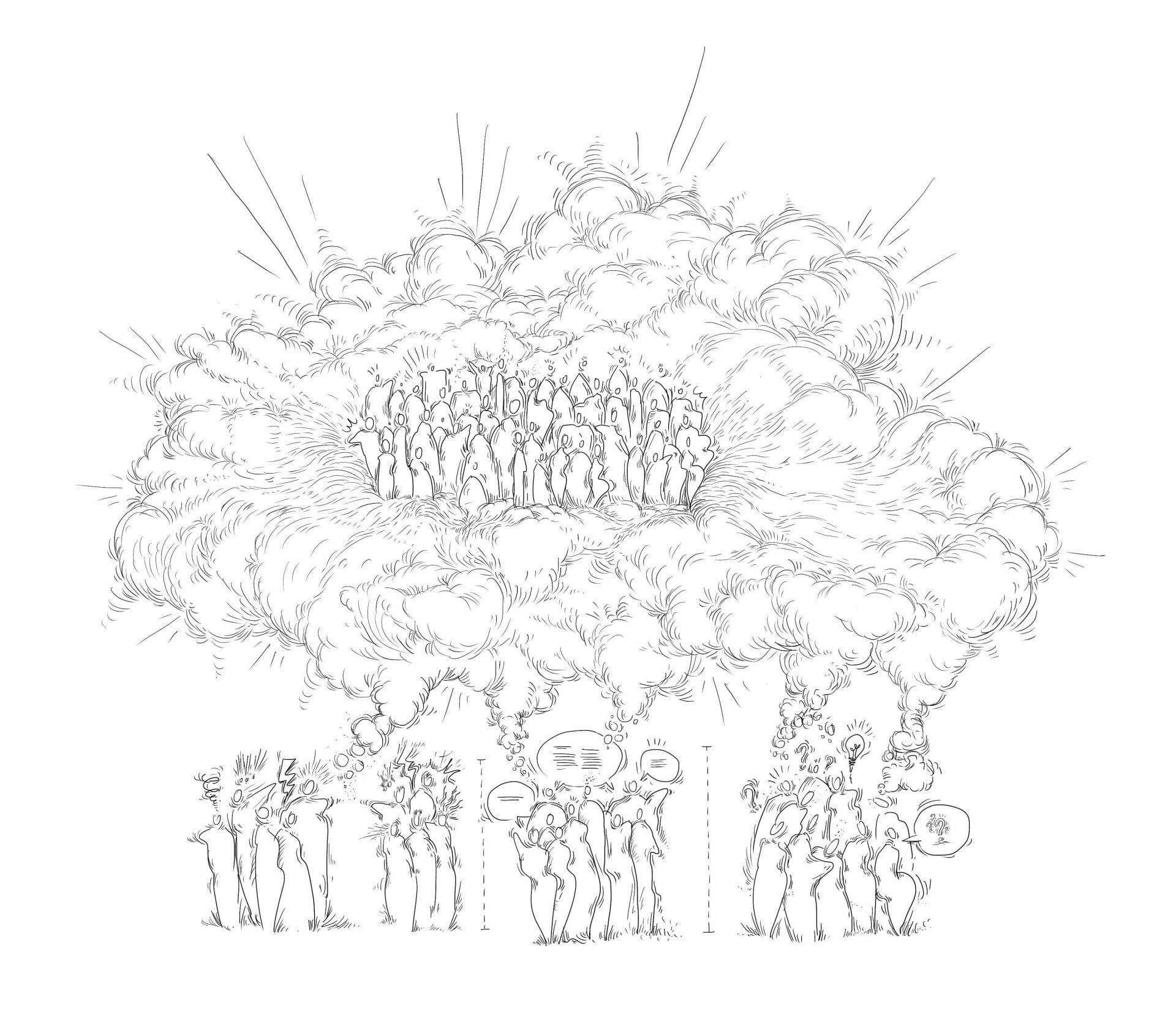

Our collective trajectory is different now than it was just weeks ago. Not only is global confinement accelerating pre-existing trends (digital transformation, remote working, localised supply chains, self-sufficient production, urban exodus, mass-surveillance), but it is magnifying fundamental systemic flaws.

We live in a narrative that prioritises productivity over self. The global over local. Private property over shared spaces. Economics over ecology. Personal interest over collective perspectives. Now that the world has come to a pause, not only can we see the inherent limits of our former ways to live and work, but also new unexpected opportunities for systemic change.

As an architecture and design studio, we are sensitive to societal changes and the drivers behind them. Post-confinement, how will our relationship to cities be affected? What new collective narratives are emerging? How will this impact our relationship to work? How can we design new habitats to accompany and bring out the best of our new ways of life? To explore what our habitats can become after confinement, we will unfold and interrogate these changes through five key frames.

The end of work

For the last half-century, we have tried to make our offices feel like home. Today, we are seeing this trend reverse. In 2019, 56% of women and 43% of men in France considered remote work to be “a positive factor for wellbeing.” The big question is how do we make this shift without losing a piece of ourselves in the process? The ability to work from everywhere has already impacted the home, public spaces, and offices, but also mindsets: deciding when and where to work is a cultural shift that reflects a will to question the importance of work in our lives, as well as the notion of productivity.

At the core of our contemporary system, one’s productivity is proportional to their financial retribution. With structural unemployment, AI peering over the horizon, and more and more jobs disappearing, this current conception of work seems illusory at best. How can we design our spaces to help us adapt to work from anywhere? What if we decoupled our traditional relationship between money and productivity? What if we adopted whole new systems and relationships to work?

Work is becoming more and more decentralised but increasingly networked. Flexibility is the new shape of work. Empowered by laptops, digital toolsets, and a knowledge economy, entirely new ways of working continue to emerge. While our communities are becoming more fragmented, this shift has enabled modern lifestyles to become increasingly self-made, independent, mobile, and globalised.

This change in values gave rise to the freelancer workforce. Today, over 40% of the global workforce is made up of freelancers, compared to only 6% in 1989. Autonomy and being able to decide when and where one works is a trend companies can no longer ignore. Already in 2019, 56% of women and 43% of men considered remote work to be “a positive factor for wellbeing.” Over 48% of them held remote work as an expectation of their company. While many old-school businesses have been reluctant to follow this trend, the global confinement—where social distancing is a fact—has officially brought us the era of remote work.

This transition to remote work will not be seamless. The thin line between work-life and private-life is becoming increasingly blurry and challenging to balance. As we move into new uncharted relationships to work, new questions about the roles of space and designs emerge: to what degree can we bend this boundary between work and life and preserve our wellbeing? How can we design our spaces to help us adapt to working from home without losing a piece of ourselves in the process?

For the last half century, we have tried to make our offices feel like home. Now we are seeing this trend mirrored. As we have all experienced, confinement has exposed the limits of our private spaces. We have all modified our space to make it ‘workable’.

Most homes were never designed or thought to ever accommodate work, leaving us to re-appropriate patio tables, dressers, attics, garages, backyards, terraces and dining rooms to accommodate our new daily rhythms – and in best case scenarios, to be able to work from home comfortably.

According to the International Organisation of Labour, by March 2020, 4 billion people were confined at home, while 2.67 billion people have been affected by a total or partial closure of their workspace. Suffice to say, we are about to see a dramatic shift in the way new homes are designed and existing ones are renovated.

Beyond home, this ability to work anywhere will impact others familiar spaces like the office. We will need less office spaces. Today, in Paris, offices represent 17 million m², compared to 95 million m² of housing. As the home becomes the new office, we could think about other usages of those spaces, by transforming them, for example, into residential living to help on the housing crisis front. But this shift in architectural function extends well beyond the physical transformation of our workspaces.

Mindsets are changing: Deciding when and where to work is a cultural shift that reflects new questions on the importance of work in our lives. In the long view, it is possible that a non-work-centric society might emerge. For more and more people (who have a job), work appears to serve little or no purpose, while for another part of the population, if it serves purpose, it is poorly compensated.

In global confinement, we see how unequal this retribution for work is: ‘essential workers’, who make up the backbone of our societies are vital —and not only in times of crisis—are poorly paid and at the end of the social ladder. According to Gene Sperling, national economic adviser to Presidents Clinton and Obama, the median pay for nursing assistants and orderlies tending the front lines in US hospitals is 14.25 dollars per hour.

Farm workers, making sure we have food, earn 12 to 14 dollars per hour. Despite how critical such work may be to support the society as a whole, the income of these roles is disproportional to their importance. At that, undervalued essential work concerns women far more than men: in France, women represent 91% of hospital care takers, 83% of primary school teachers, 90% of senior care centres employees, 90% of cashiers and 97% of homecare workers. How could we design a different relationship between work and income to overcome these forms of inequality?

Work as we know it today is threefold: Work is a way of earning money to survive; work is a way to define our personal identity; work is a way to contribute to our collective trajectory. At the core of this system, one’s productivity is proportional to their financial retribution. With structural unemployment, AI peering over the horizon, and more and more jobs disappearing, this current conception of work seems illusory at best.

The question we must all ask ourselves is: What do we want to do with our time? What if we switch from working to earn money to survive and consume, to an activity based contribution to the society? Today, there are many ongoing experiments exploring the concept of Unconditional (or more commonly ‘Universal’) Basic Income (UBI). Economist Jeremy Rifkin puts it very simply: “[Unconditional] Basic Income is not a utopia, it’s a practical business plan for the next step of the human journey.”

UBI is one of the most ambitious, yet promising, systemic experiments being explored today. Whether privately funded or government backed, UBI redistributes wealth, by providing people a monthly income – no strings attached. This system has already been experimented across four continents, spanning wealthy and developing economies. The first pilots appeared in the US in the 60s and 70s. Finland became the first European country to launch a government backed programme in 2017. Namibia tested in 2018, as well as the Netherlands. The question that is often asked when it comes to UBI is: would people still go to work? Would we just become complacent or lethargic with our time?

So far, these experiments have shown that when people feel more financial security, they are happier, healthier, and more eager to create things. This shines light on two fundamental topics: personal behaviour and what we collectively consider productive or not. A 2013 study by the World Bank showed that when directly given cash, poorer individuals don’t waste it on tobacco and alcohol.

In fact, it has shown the contrary: the richer you are, the more you consume alcohol and drugs. A test-run conducted in Canada in the 1970s showed that only 1% of UBI recipients stoped working – mostly to take care of their children. On average, people reduced working hours by less than 10%. The extra times tends to actually be used to consolidate or learn new skills, look for better jobs, or open a business. For example, in Namibia’s 2018 UBI pilot, entrepreneurship rose over 300%.

While the world has gotten far richer in recent years, inequalities have also become more extreme. This is not news: wealth is almost exclusively being consolidated by the richest few individuals. Today, 26 people now have as much money as the poorest 3.8 billion people on the planet. The wealth inequality gap is has never been so boundless. And many argue, even in conservative camps, that it might be time to distribute the spoils more evenly to preserve social peace.

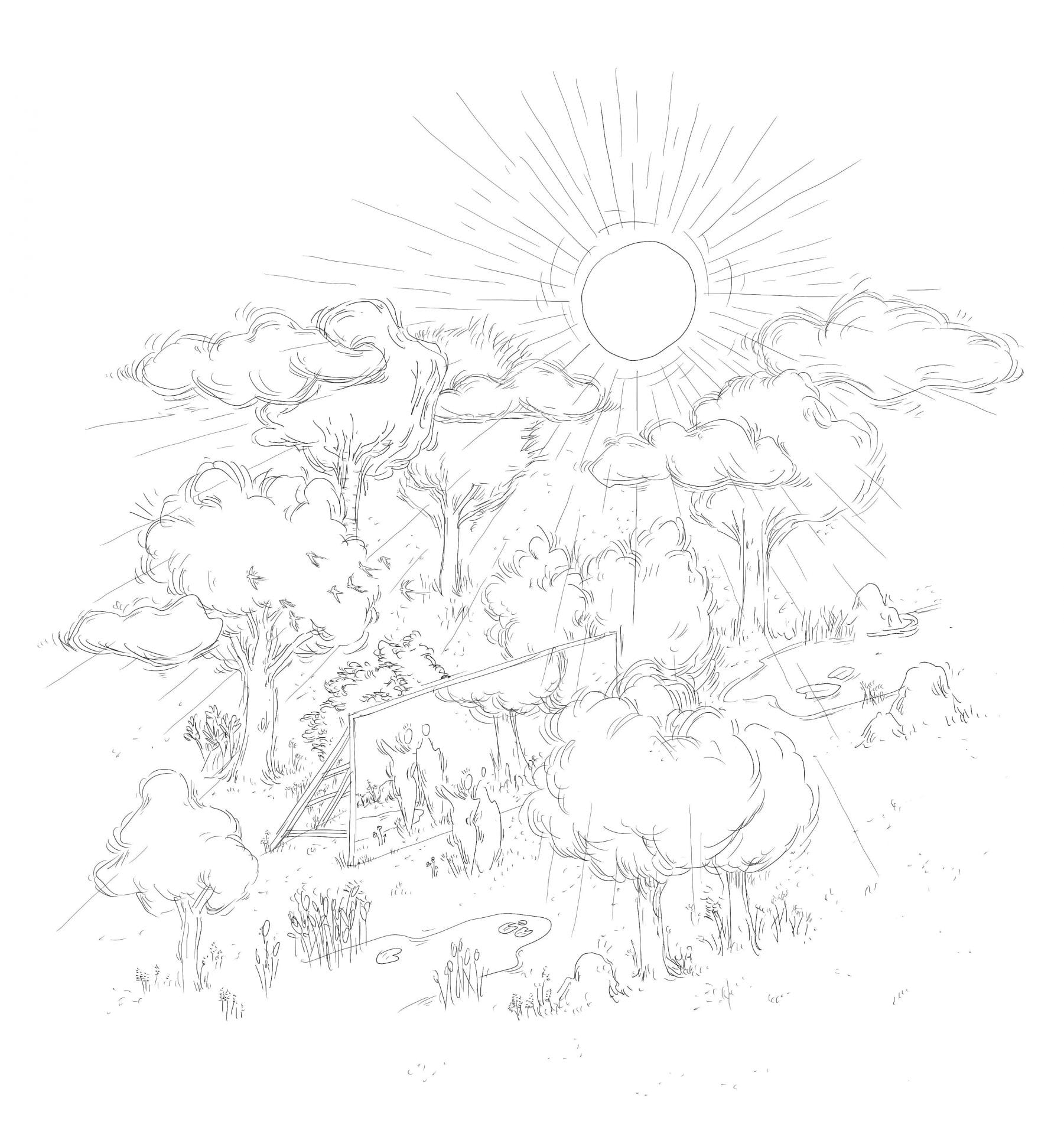

What is at stake here is how to both distribute the productive wealth of society and reinvent the notion of our personal sense of purpose within society. If we manage to decouple productive output from financial return and can replace our traditional sense of productivity with self-created, meaningful work, new relationships to our immediate habitat and the broader territories will emerge.

The focus would flip from traditional workspaces into new kinds of places open to unexpected collaboration, productive idleness, and novel activities. Until today, the central purpose of cities has been to gather around productivity. How might the city evolve if we see such a radical shift in this centralised logic? To what degree will we see a second wave of the coworking movement, better equipped to adapt to times of great uncertainty or sudden re-confinement?

New ways to live and work

Each of these five perspectives, from urban to personal scales, have reoriented our studio vision and given our practice new bearings. Moving forward, the world we want to build is one:

Where we are not only bound to dense urban environments, but where we can continuously explore different formats of lifestyles across territories. Where we recognise that collaborating upon differences is our most powerful capability. Where our habitats encourage this core ability, rather than inhibit it. Where we no longer only work for money, but contribute to a ‘creation society’, untied from economic survival.

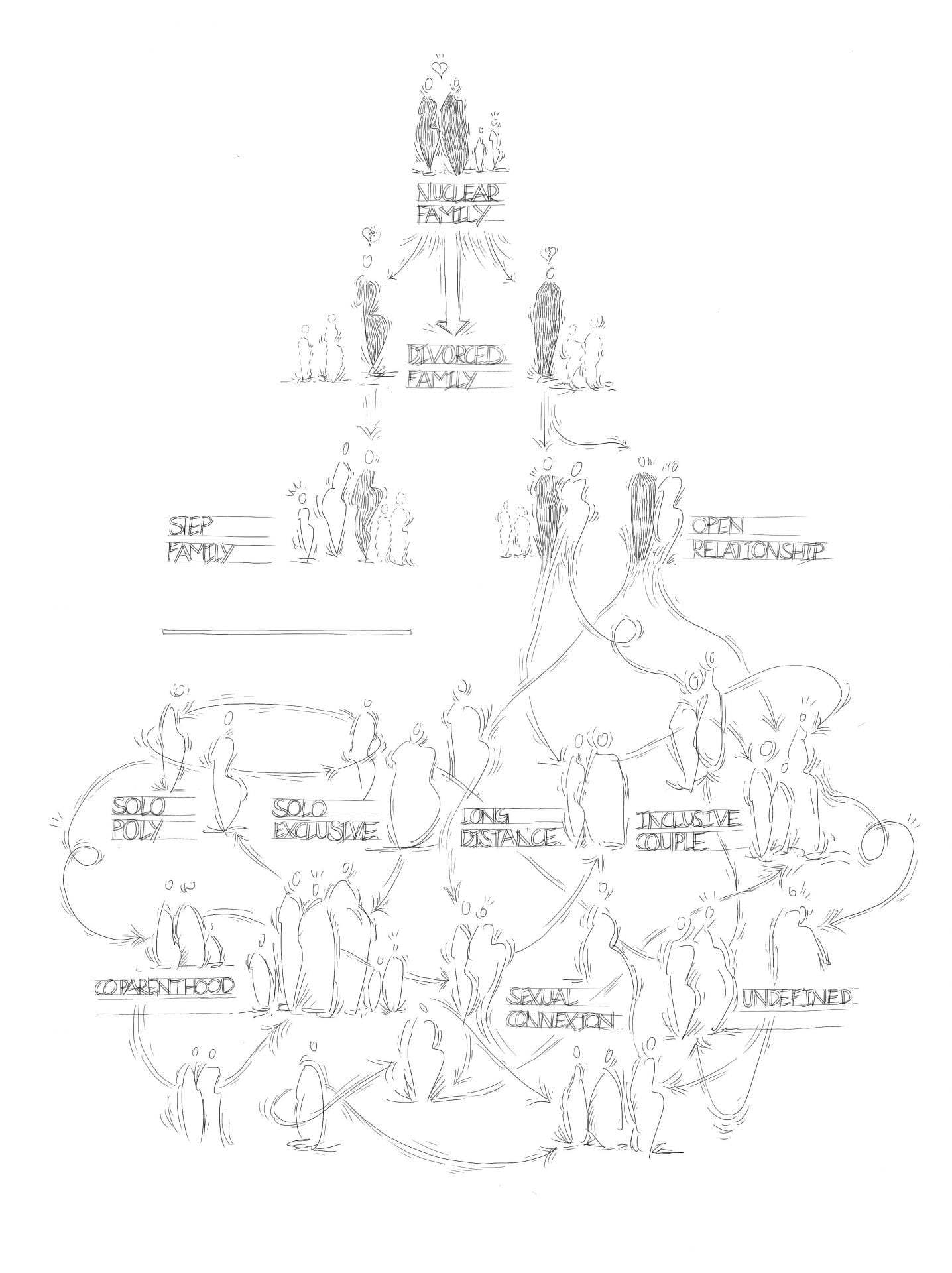

Where relationships and families are chosen, liquid, and adaptive, and where our habitats enable these dynamics. Where the family is no longer only built upon inheritance and transmission of culture and wealth. Where we are ready to live as a part of nature instead of believing we are apart from it. Where our environments are also built for the other (non-human) beings with which we share our habitats.

For more information visit cutworkstudio.com

All images courtesy of Cutwork. Illustrations by Yuji Maeno